Robert Roberson absent from hearing before Texas lawmakers after his execution was halted

Texas lawmakers were expected to hear testimony at the state Capitol on Monday from Robert Roberson, a death row inmate whose execution was temporarily called off last week. But Roberson ultimately did not appear before the legislative panel as planned, after Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office refused to let Roberson give testimony in person, citing security concerns, and the legislature declined to have him appear virtually because of his autism and lack of familiarity with modern technology after more than 20 years in maximum security prison.

The Texas House Criminal Jurisprudence Committee said it was pushing back against Paxton’s decision in hopes of allowing Roberson to testify in person at a different time.

“I expect a quick resolution to these discussions, which are ongoing at this moment,” said Democratic state Rep. Joe Moody, the chairman of a state House committee that led efforts to stop the execution, at Monday’s hearing, referring to talks with the attorney general’s office. “I will update everyone as soon as those plans are finalized.”

Moody noted the subpoena that sought the inmate’s testimony remained in effect and could be enforced “dramatically,” if the committee chose to be heavy-handed. Although, given the spate of conflicting moves from a range of agencies in Roberson’s case, the chairman added: “We aren’t interested in escalating a division between branches of government.”

Roberson, 57, had been scheduled to die by lethal injection Thursday for the killing of his 2-year-old daughter, Nikki Curtis, in 2002. But as scientific developments in recent years called into question fundamental aspects of his case and conviction, authorities started to question his guilt. Roberson was convicted of capital murder in his daughter’s death from shaken baby syndrome, a condition once used as evidence of child abuse that experts now consider outdated and too vague to support a criminal charge.

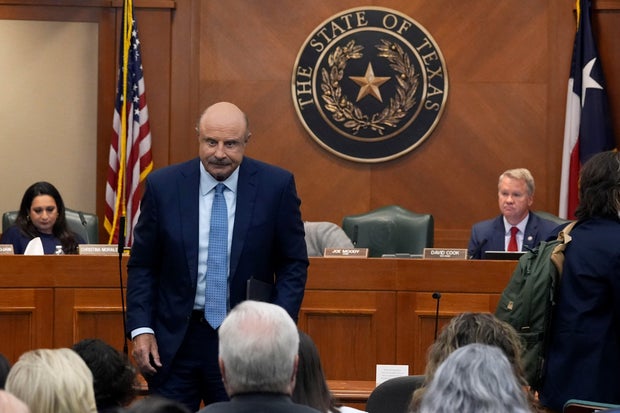

At Monday’s hearing, Phil McGraw, the television host known as Dr. Phil, who has a doctorate in psychology, testified there were flaws in the medical evaluation of Roberson’s daughter when she died, which followed a period of documented illness and a drug prescription that may have caused her to deteriorate quickly.

“There’s no such thing as shaken baby syndrome,” he said, arguing the traumatic head injury it intends to define would accompany “very clear signs” of abuse by an adult “that were not present in this case.”

During his testimony, McGraw said he believes Roberson has “not had due process. I don’t think he’s had a fair trial and I think he should.”

Donald Salzman, pro bono counsel at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom and a former public defender in Maryland, said the medical records, trial transcript and expert opinions were “infused” with shaken baby syndrome.

“When you read the transcript in this case, I think it’s very clear what the jury heard: Outdated, unverified, unreliable science that was presented to the jury as fact. It was essentially, as this committee has expressed, it was a diagnosis of murder,” said Salzman, who was not testifying on behalf of his firm.

Evolutions in how scientific and medical communities understand the syndrome and its symptoms have led to at least a dozen exonerations in the United States over the last couple of decades. But prosecutors and the courts argue there is evidence of Roberson’s guilt outside of Curtis’ diagnosis, even as the lead investigator who helped convict him of murder has openly proclaimed the man’s innocence and acknowledged his office’s own errors in judging Roberson’s behavior before learning of his autism.

Texas state Rep. Jeff Leach, a co-chair on the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, shared similar sentiments in his opening remarks at the hearing. Leach said he came to believe Roberson is “fully innocent” shortly after meeting the inmate.

“The purpose of this hearing … is to ask questions and to find the truth. To figure out where the system went wrong, where it failed Nikki and where it failed Mr. Roberson,” Leach said.

Roberson maintains he did not kill his daughter. He would be the first person in the U.S. put to death for a conviction linked to shaken baby syndrome if his execution ends up moving forward.

Hours before it was set to take place Thursday, a Travis County judge granted a temporary restraining order to pause the procedure, so that he would be able to testify before a bipartisan group of state lawmakers on the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee. The committee had one night earlier subpoenaed Roberson to give testimony at the hearing, addressing “criminal procedure related to capital punishment” and a landmark “junk science” law that should allow Texas inmates to appeal their convictions when the scientific or forensic evidence used to convict them has been debunked or determined unreliable.

The subpoena came on the heels of a recommendation by the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles earlier in the day denying Roberson’s request for clemency, effectively preventing Gov. Greg Abbott from granting clemency without the court’s intervention. Abbott could still delay the execution by 30 days through an executive reprieve.

Abbott has urged the Texas Supreme Court to toss out the subpoena ordering Roberson’s testimony. The governor’s general counsel said in a letter to the state’s highest court that the House committee “stepped out of line” by issuing a subpoena that ensures the execution is delayed at least 90 days. It suggested the committee’s “tactic” essentially opens the door for “rewriting the Constitution to reassign a power given only to the Governor.”

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals went on to reverse the county judge’s temporary restraining order. Then, as the U.S. Supreme Court denied a request for a stay of Roberson’s execution — with Justice Sonia Sotomayor writing in her ruling that the “Supreme Court is powerless to act without a colorable federal claim” — the Texas Supreme Court halted the execution. Its eleventh-hour decision granted a civil appeal filed by Roberson’s attorneys and state lawmakers.

“Whether the legislature may use its authority to compel the attendance of witnesses to block the executive branch’s authority to enforce a sentence of death is a question of Texas civil law, not its criminal law,” Texas Supreme Court Justice Evan Young said in his opinion.